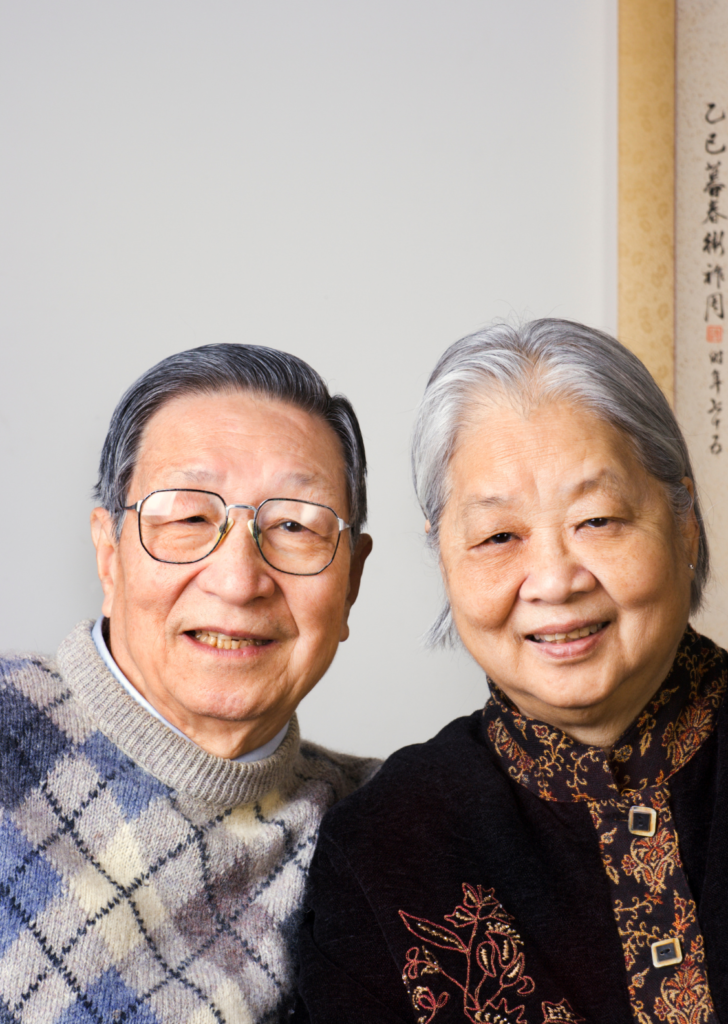

In conversations about aging and dementia, especially when it comes to sensitive topics like sexual consent, the focus tends to fall on what’s been lost—cognitive decline, confusion, and the inability to remember or communicate as before. While these challenges are undeniably real, there’s another side that often goes unnoticed: what still remains. This is where a “salutogenic” approach comes into play, one that encourages us to rethink how we view older adults, dementia, and sexual consent.

Salutogenesis, in essence, shifts the focus toward the factors that support health and well-being rather than those that cause disease. Unlike the more familiar “pathogenic” approach, which focuses on diagnosing and treating illness, salutogenesis emphasizes potential and resilience—focusing on the elements that help individuals maintain their health, even in challenging conditions. Applied to dementia and sexual consent, this means we move away from concentrating solely on the losses people with dementia experience. Instead, we begin to pay attention to what they can still do—their ability to feel, to connect, and to express themselves. It’s about recognizing their dignity, honoring their remaining strengths, and seeing the potential for autonomy that persists even in the face of cognitive decline.

Too often, we reduce individuals with dementia to a collection of symptoms, but dementia doesn’t erase the basic human need for emotional connection, intimacy, or love. And it certainly doesn’t strip away a person’s right to be treated as a whole individual. When it comes to sexual consent, narrowing the conversation to what’s been lost—whether it’s memory or decision-making capacity—leads to a restrictive view that doesn’t serve the person well.

Instead, we need to acknowledge that people with dementia may still be capable of expressing consent, desires, and boundaries in ways that go beyond traditional verbal communication. Emotional responses, non-verbal cues, and expressions of affection all play a part in conveying intent, and these should be considered just as valid as verbal expressions.

This is why it’s so critical to look beyond the disease and see the individual behind it. What emerges is a person who, despite the challenges they face, may still desire and deserve the opportunity to experience intimacy and form relationships. The key lies in recognizing what they can do, rather than focusing on what they can’t.

Moving away from a deficit-based model—where the focus is on impairments—toward a salutogenic approach allows us to see the potential that still exists in people with dementia. This change in mindset can deeply influence how we address complex issues like sexual consent. When caregivers and families focus on the strengths that remain—whether it’s the ability to recognize a partner, hold hands, or seek out affection—opportunities for meaningful connections emerge. Focusing on potential also allows for a more nuanced approach to sexual consent, one that respects various forms of expressing desires and boundaries.

By seeing people with dementia as more than just their diagnosis, we honor their individuality and respect their humanity. Every person’s history, preferences, and relationships are unique, and care should be tailored to reflect that uniqueness, not a one-size-fits-all solution.

This shift in perspective also moves the conversation about sexual consent from a strictly legal or medical framework to one that is more person-centered. It’s less about rigid rules and more about understanding each individual’s capacity for consent, considering their context. What does this person need to feel valued? How can we support their abilities while ensuring their well-being? These are the questions that need to shape our approach.

Ultimately, focusing on their potential isn’t just about advocating for sexual rights—it’s about advocating for their humanity.